Sickness and Death in Roman London

In the 1st century, Londinium was a real Roman wild frontier. It was probably populated by a large number of immigrants from all over the Roman Empire alongside native Britons, probably traders dealing in goods for the Roman market, travellers en route to other parts of Roman Britain, military personal and government officials serving a fixed term of duty.

Health is controlled by many factors including access to health care, diet, genetic predisposition to certain illnesses, and most importantly, environment. Living in an urban environment during the Roman period exposed the population to infectious diseases easily transmitted by close contact with people, animals and insects, industrial pollutants and accidents in the work place, new infections carried in by migrants, contaminated water supplies, rotting domestic and industrial refuse that attract disease carrying animals, squalid and densely packed housing without adequate ventilation or toilet facilities, poor quality imported food and poor personal hygiene – not to forget the dangers of physical assault, fire and war. Lives of the inhabitants of Londinium were plagued with ill health and disease. It seems the reality of Roman urban life in the city was far more dangerous and disgusting than images of nice stone bath houses and well-dressed inhabitants would allow us to believe.

Environmental evidence

An excavation by MOLAS at 1 Poultry in the City of London, uncovered over 70 buildings that had been constructed and rebuilt over a total of 350 years. The early buildings excavated were timber-framed with mud brick or wattle and daub fill. Houses were generally built of timber with thatched or boarded roofs. The houses at 1 Poultry had narrow road frontages with shops at the front and small rooms behind, thatched roofs, compacted earth floors and small back yards. The rooms were roughly 2.5 metres square, and the shop keepers would have probably lived in their shops as well. The conditions would have been incredibly cramped, and without proper ventilation, these conditions and the use of open fires for cooking and heating would have led to respiratory diseases and sinus problems. Winter would have been very grim indeed. Indoor air pollution from soot and dust particles cause chronic respiratory problems, such as bronchitis, heart disease and lung cancer. Modern studies of indoor smoke pollution in third world countries indicate clearly that women and children are disproportionately affected by indoor cooking and heating, as they are responsible for running the household. In Romano-British patriarchal society, women were expected to be home makers – therefore must have been prone to higher incidents of respiratory disease, as well as bearing the burden of frequent pregnancies. For most women, early death in these environments must have been an occupational hazard.

Few houses would have had their own toilets and human waste was probably thrown in roadside drains, the Walbrook stream which ran close by, or dumped in the back yards. Samples of soil from the tiny gardens at 1 Poultry contained a large number of house fly and horse fly pupae which show that rubbish was rotting there. Pigs, chickens and other domestic animals were also kept in the tiny back yards and other outbuildings, with dung heaps adding to the filth (and smell). The houses and associated rubbish would have attracted foxes, rats and house mice. Wells dug near the houses would have been contaminated by the rubbish, human faeces and animal waste – an ideal growing medium for dysentery, cholera, typhoid, amongst others. Exposure to the chemical by-products of industries such as tanning, dyeing or metal working could have caused lesions and tumours to develop, as well as superficial skin complaints and sores.

Personal hygiene

Parasites were unlikely to have been recovered for the East London Roman Cemetery due to soil acidity and lack of waterlogging. However, parasites found on other sites in Britain, such as Poundbury in Dorset, suggest that personal hygiene was not always at the foremost of most peoples minds – despite the appearance of bath houses in many Roman settlements in Britain.

Personal hygiene appears to have been sufficient to let wounds heal without turning gangrenous. Interestingly, teeth from male skeletons were in a worse state than females, suggesting that women had better personal hygiene. Pubic and hair lice have been found, and whipworms and round worms have been found in faecal deposits. Human worms can cause anaemia, and cribra orbitalis which can be seen in human bones.

Roman bath house at Shadwell

A large Roman bath was excavated by Pre Construct Archaeology in 2003 on The Highway, Tower Hamlets, not far from the Prescot Street site, one of a dozen or so known from the city of Londinium.

It stood on the side of one of the main Roman roads out of the city, and was constructed sometime in the 2nd century. It had 5 rooms heated with a hypocaust and a cold plunge pool. The building stood to the side of a series of structures interpreted as an inn, where lots of finds such as coins, jewellery and hairpins were made.

Diet and health

It is possible to recognise many diseases and injuries in skeletons where the skeleton or teeth have been affected. Unfortunately, few diseases or injuries actually create recognisable changes in bone or tooth, and poor preservation makes it difficult to diagnose any illness or disease.

Food is essential to maintain a healthy body and immune system. Without easy access to fresh food, many of the poorer residents of Londinium may not have an adequate diet, and would have suffered from malnutrition as a result.

Malnutrition can cause a number of diseases and conditions. It is a major cause of severe mental impairment, vitamin deficiency illnesses such as scurvy, rickets, spina bifida, and iodine deficiency.

However, within the areas of the East London Roman Cemetery, only around 5% of the skeletons showed signs of cribia orbitalis, indicating an iron deficiency caused by poor nutrition, parasites or diarrhoea. Vitamin C deficiency did not appear to be endemic in the population of the East London Roman Cemetery, although some evidence of a lack of fresh fruit and vegetables is evident. One infant skeleton showed signs of scurvy, and several adult skeletons showed signs of the early characteristics of scurvy such as periodontal disease.

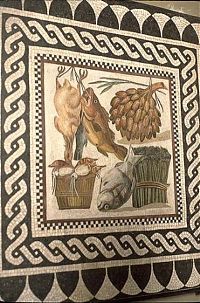

Mosaic depicting food including fish, seafood, a plucked chicken, and two kinds of vegetables from the Vatican Museum Gallery of the Candelabrum, Rome

Londinium was well supplied with road and river routes from it’s hinterlands for the import of food and grain. It imported foodstuffs from all over Britain and the Empire. Oysters were a staple part of Londinium’s diet. Fruit such as grape, and figs were eaten, and their seeds are found all over the town. It would seem that most inhabitants of Londinium ate a relatively balanced diet, but a small percentage of the population would have had a poor diet in terms of amount and quality and some of the children had periods of serious illness, that affected their growth. Some of the population were well fed – two skeletons from the East London Roman Cemetery showed signs of gout, a hereditary inflammatory disease that can be exacerbated by a diet rich in meat, fish, poultry, dairy products and alcohol. It is almost always a condition suffered by older males. The majority of injuries appear to have been sustained through accidents rather than violence. There is skeletal evidence for repetitive-strain injury damage, and damage to tendons and ligaments in areas of the body identical to modern injuries sustained through horse riding.

Medicine and Surgery

Roman military units had access to doctors, surgeons and medicines. Urban centres tended to be located close to military stations and this may have allowed civilians some access to military medical services. Bathing was also popular for curing illness, especially to aid painful joints, lead poisoning, liver and kidney disease and skin conditions.

There is evidence for surgical treatment at other cemetery sites in Britain. Trepanation, or surgery to create holes in the skull, seemed to be used, and cases of dentistry and treating fractures with metal plates have been found in cemeteries at York, Chichester and Cirencester.

Burials and diseases at West Tenter Street

The bones from the burials at West Tenter Street were examined to determine age at death, sex dental health and height. Amongst these skeletons, 7 were infants under five, 17 aged 5 to 15 years, with 57 adult males and 26 adult females. The majority of those assigned an age had died before they were 45 years old.

Diseases and injuries at West Tenter Street

Whytehead’s excavation at West Tenter Street revealed that roughly two-thirds of the adult skeletons had some form of injury or disease affecting teeth, bone or joint. Degenerative diseases of the joints were very common. No sign of disease could be found in the inhumed skeletons aged 15 and under. The largest amount of recognisable changes were caused by dental problems; tooth decay, dental abscesses, disease of the bone holding the teeth in place (alveolar disease), and impacted wisdom teeth. A quarter of all adults suffered some form of dental disease.

13 skeletons showed signs of trauma – fractures to one or more bones. These fractures include broken ribs, collar bones and fibulae, one broken radius and ulna and one crushed lumbar vertebrae. The majority were well healed and realigned. The fracture of the radius and ulna belonging to a male is typically sustained whilst protecting the head from a blow – the fracture had never healed properly before death and would have caused the forearm to ‘flap’ about painfully. It is unlikely to have belonged to a professional soldier, as they would have been able to access military medical attention.

One female skeleton showed signs of cuts on the vertebrae of her back, which could have been made by a weapon just before or after death, as there was no sign of healing. The weapon would have been plunged deeply into the stomach to cause such injuries and would have caused massive internal bleeding if the person was still alive when they occurred.

10 skeletons showed some form of congenital abnormality. One suffered spina bifida occulta , although this would not have been visible during life. Four skeletons showed evidence for spondylolysis which causes the 5th lumbar vertebra to become separated from the body. This can be genetic, although it usually occurs due to stress on the bones due to activities such as weight lifting or strenuous exercise. 3 skeletons showed evidence of an infection called osteomyelitis, which is an infection of the bone or bone marrow and causes lesions on the bones. This can be caused by localised trauma to the bone, infection anywhere in the body that spreads to the bone marrow, or through infected teeth.

Lead levels and lead poisoning at West Tenter Street

Lead poisoning was extremely common across the Roman Empire. The levels of lead in the bones at West Tenter Street were sampled and examined during the excavation. This demonstrated that the levels of lead in those people buried in the cemetery were twice as high as that found in the modern adult population of London. This is probably due to lead water pipes in the Roman town and the fact that it was common to prepare food and drink in lead-lined or pewter vessels. Symptoms of lead poisoning include nausea, stomach pains, neurological and cognitive impairment, even seizure and coma.

Hence gout and stone afflict the human race

Hence lazy jaundice with her saffron face

Palsy, with shaking head and tott’ring knees

And bloated dropsy, the staunch sot’s disease

And sharpened feature, shew’d that death was nigh

The feeble offspring curse their crazy sires

And, tainted from his birth, the youth expires

(Description of lead poisoning by an anonymous Roman hermit

translated by Humelbergius Secundus, 1829)

Human remains from the Prescot Street evaluation

Samples of bone were taken from Prescot Street for analysis during the evaluation in 2006. Nine samples were of cremated bone, which did not reveal any physical problems that could be identified from bone alone. The two full inhumations were left in situ for the full excavation. Sampled bones from Trench 3 belonged to a male, with indications of some wear and tear on the joints of the leg and foot and the loss of two back teeth before he died.

- Author: Lorna Richardson |

- Jul 23, 2008

- Share